|

Working for a Living

Text and photos by Dwight Cendrowski

It's midmorning at the Washtenaw County Recreation Center. Mark Snyder stops vacuuming the hallway as co-worker David Fluker heads into the custodian's closet. With a mischievous glint in his eye Mark reaches over and shuts the door, then laughs loudly as David comes out smiling.

Ask anyone at the Recreation Center to describe Mark, and they'll tell you a story like that. "A jokester. A tease. The man with the vacuum and that great big wide smile."

Mark is one of ten disabled adults doing custodial work for the center as part of a community employment program through the Development Center, a program of Washtenaw County's Human Services Department. Located in Ypsilanti, the Development Center serves 220 developmentally disabled adults, providing work experience in basic materials assembly and training people for employment in the workplace.

By the time the Recreation Center on Washtenaw in Ann Arbor opened in September of 1991, several disabled people had been approved to work there. They first received training in janitorial services at the Development Center. "And the pay rate was set after a wage survey," says Bill Obenaus, center supervisor. " So that they're paid what others would be paid doing similar work."

And work they do. "They do a tremendous job for us," says Fred Barkley, the Recreation Center's director. "We're able to keep the building clean and provide jobs. Of course, Mark's the favorite." It's easy to see why.

"He's always smiling," says Jan Marble, community relations coordinator for the county Parks & Recreation Commission. "Every morning he comes in to say hi. It's been a great experience for all of us who work here to know Mark and appreciate his special abilities." "He's always smiling," says Jan Marble, community relations coordinator for the county Parks & Recreation Commission. "Every morning he comes in to say hi. It's been a great experience for all of us who work here to know Mark and appreciate his special abilities."

Mark can vocalize, but is hard to understand. He's had cerebral palsy from birth and uses a special wheelchair he navigates with his feet. His movements can be quick and jerky.

Mark's job is to vacuum all the carpeting on the main level of the Recreation Center. Starting with the main entry, he moves down the hallway, then into the weight room, and on to the seating and refreshment area. Holding on with a strong left hand, he moves methodically forward, then reverses, see-sawing across the floor. He also dusts the columns and main desk.

Anne Goodell supervises Mark and the rest of the work crew . She says the program benefits everyone. "Public awareness is a big plus. A lot of people have not been around handicapped people before. And we've had a good response. They handle all the janitorial services: vacuuming, dusting, cleaning of restrooms and lockers, and emptying trash."

"It's been an unqualified success," says Bill Obenaus. "A guy like Mark could really become insulated and left behind. This job makes him a tax-paying citizen, gives him self-esteem. Mark is bright and active. He understands everything. But he is challenged by the spasticity."

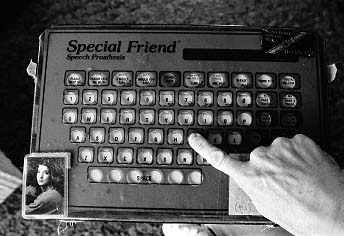

Communication is another challenge for Mark. He uses a speech machine with a computer generated voice that mounts on his wheelchair. Besides yes and no, he can push a button to pronounce foods, names of clothing and other items, and emotions like angry or scared. But more often he just points to make his needs known.

Linda Taylor is Mark's social worker through Community Mental Health. She describes him as a very capable and social person who likes to laugh. Mark did assembly and materials handling work at the development center before his current job. "He took the initiative," says Ms. Taylor. "He could think ahead and look out for the lower functioning client."

Ms. Taylor included Mark's name on a list of names she thought would do well at the Recreation Center. "He's an excellent worker, takes direction, and is always there. People have a need to feel useful and productive, to say `I can work and earn a paycheck.' I can't tell you how many parents tell me how much better their children are doing in these work programs. There's a sense of pride."

Mark will soon turn 40. He lives in the Ann Arbor home of his father, Carl Snyder, a retired professor of Labor Economics at Eastern Michigan University. Mark lived with assistance in his own apartment for a time, but had recurring problems with a roommate and services. Finally, when his mother died in October of 1992, he decided to come back home. "His mother was the central person in his long developmental journey," says Mr. Snyder. " It took a while to get through the grief." Mark will soon turn 40. He lives in the Ann Arbor home of his father, Carl Snyder, a retired professor of Labor Economics at Eastern Michigan University. Mark lived with assistance in his own apartment for a time, but had recurring problems with a roommate and services. Finally, when his mother died in October of 1992, he decided to come back home. "His mother was the central person in his long developmental journey," says Mr. Snyder. " It took a while to get through the grief."

After being off work for six weeks, all his fellow workers joined in to send him a card and asking him to come back. He's seldom missed a day since.

This frigid February morning Mark wakes at 6:30. He moves to the bathroom where his father shaves him. He then rolls down the hallway to the kitchen. The hall is extra wide, one of the features Mr. Snyder built into the house in 1961 with Mark and his wheelchair in mind. Mark eats a sweet roll while his father heats up his cocoa wheat cereal. Eating takes extra time. Chewing is difficult for Mark, and his movements need to be deliberate to counter the arm tightness and spasms.

While his father cleans his glasses, Mark lowers himself from his chair to put on his white socks. He methodically opens the tube opening, then slowly works the sock over the heel and up the ankle. Each sock  takes close to five minutes. Then more time for the velcro fastened shoes. takes close to five minutes. Then more time for the velcro fastened shoes.

The work program supplies uniforms for Mark and the others. Red shirts and gray pants. Just recently they've begun trying shirts with velcro instead of buttons for Mark, but getting the shirt on is still proving difficult. Pre-fastened and brought down over the head, all the clasps come loose, and Mr. Snyder laughs as he promises to try it another way tomorrow. It's not yet 8:00, and Carl has only to put in Mark's hearing aid and snap on the keys he wears on his belt. They're ahead of schedule today. Mark pulls on his heavy, red winter coat, and when the Ann Arbor A-Ride rolls up at 8:20, he grabs his lunch pail and rolls down the driveway to the bus.

"Mark really enjoys his job," says Mr. Snyder. "It gives a structure to his day. He works four hours and gives him an income. He saves some and spends some."

Mark recently bought a boombox, which he uses to feed his passion for country music. A long row of his bowling trophies lines the expansive living room windows. He loves watching the weather channel, taking in concerts, baseball, and fishing at the family's cabin up north. "He's a very responsive, perceptive person," says Mr. Snyder. "Friendly, outgoing, and affectionate. And he has the ability of making people feel happy."

At work, Mark is concentrating on the carpet. He purses his lips and breathes heavily, showing the effort of moving around the vacuum. Occasionally people will say hi and pat his shoulder.

Margaret Gruber comes to the Center for aerobics. She leans in and jokes with Mark, and he responds with his wide smile and loud, abrupt laugh. "He's my buddy," says Ms Gruber. She points to the wallet-sized photo of a young woman on his speech box, a former Center employee who was close to Mark, and now lives in California. "I'm waiting to get my picture on the board. You haven't made it till your picture's on the board," she jokes.

Now and then Mark will rest. He'll lower his head, or stare pensively out over the basketball court. Normally happy, he can also get irritated and distressed, sometimes over the frustration at making his wishes known. Watch his face, say many who know him. It is very expressive, at turns bright and joyful, pensive, angry and thoughtful.

There's been almost no negative feedback from any visitors or employees at the Center. Linda Taylor sees that as evidence of the program's success. "The more people have exposure to the physically and mentally disabled, the more they see they can be productive, contributing workers. And the less need for programs that keep them out of the public eye."

Bill Obenaus also praises the program and results. "These are your most dependable employees. Come hell or high water they're there, day in and day out. Nothing keeps them away. It becomes their life."

It's 1:30 p.m. Mark has put on his coat. His supervisor Anne says goodbye. Someone high-fives him and Mark smiles, jumping up and down in his seat and throwing his head back to laugh his deep throaty laugh. The bus driver is right on time, and pushes Mark into the specially equipped van that lets him stay right in his chair for the ride home.

He's working for a living. And he'll be there tomorrow at 9.

|

|

|